And I will hang my head, hang my head low

And I will hang my head, hang my head low

(The crane wife 3)

I was never one to appreciate music for production value, innovation, legacy and all the other attributes of “great legends.” I am of a more simple mind. If it moves me, I will embrace it and love it. If it doesn’t, it’ll fail.

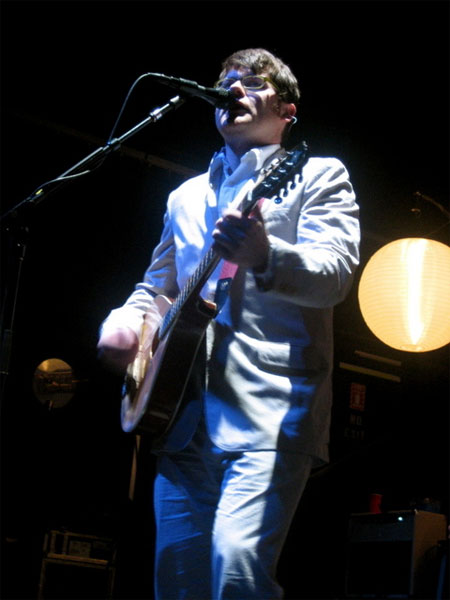

That said, nothing has really ever moved me as much as Colin Meloy and The Decemberists. This post serves multiple functions: it’s an appreciation of the band, it’s a call for people to come to Vienna and see them live in September and it’s my own private form of exorcism.

My brother in arms

I’d rather I’d lose my limbs

Than let you come to harm

(The soldiering life)

The spring of 2005 was beautiful. I had my own little apartment in Columbia, Mo., which I had decorated with all sorts of second hand and vintage furniture picked out from Goodwill or the Salvation Army. I used to wake up to the sounds of National Public Radio, stroll along the living room barefoot, and yawn in terror at the hours I’d have to devote to reporting and editing. The projects I worked on that spring, including my master’s project, won’t be matched for a quite while. I really wasn’t doing much but being a journalist and loving it. I still do that occasionally, but there was something special about those days.

I fell on the playing field

The work of an errant heel

The din of the crowd and the loud commotion

Went deafening silence and stopped emotion

(The sporting life)

My master’s project required that I write a short weekly journal detailing how my work was going. As I always do when I’m assigned to write something that is not for publication, I made it highly personal. My journals then were a struggle to define my work and the vision I had for my journalism. As corny as some of them sound, it was some of the most honest writing I have ever done. There was so much passion in every journal entry that I wonder how (and when) can I bring it all back. I wrote:

What is journalism? This question has been racing through my brain for a couple of weeks and it popped up every five seconds during a recent Missourian brainstorm meeting on the Islam story. As we went around the table, we were not only talking about various angles, ideas and approaches to the story – we were sharing and debating our definitions of journalism, our ways of telling stories.

Let me back up a little.

I have been searching for a personal definition of journalism for close to six years now. What is the goal and purpose of MY journalism? Yes, there is the mission of the profession as a whole, but whether we are conscious or not, we all have a way of interpreting and applying it. My journalism has slowly, but surely, pushed me in the direction of explanation, telling the story of the story, tackling ideas not events, having people stand in for phenomena.

All I heard was a shout

of your brother calling me out

and you ran like a fool to my side

and the shot it hit hard

and your frame went limp in my arms

and a lull of love was your dying cry

(O Valencia)

How easy it all seems when the only question that plagues your day is: “What is journalism?” Did I find an answer? Not a final one, but I did find a working definition:

What is journalism? Journalism is the ability and the opportunity to share stories of the world and the people in it with those around you.

It’s not perfect yet, but I can live with it for now. The key word is sharing. As a journalist, one has the opportunity to immerse in a phenomenon or someone’s life. He probably influenced it just as much as it influences him. And he brings back a story that hopefully explains the world a little better. (…)

Here’s an image. Journalism can be a tennis ball: fast, easy to handle, easy to look at and easy to discard. But what if journalism was a gigantic Earth shaped sphere? It would be slow, complicated, hard to handle but hard to forget about and ignore. And then a good story gives it the needed push and once it’s in motion, one can’t take their eyes off it. Every few rolls something else catches your eye and you make note of it going “wow.†The imagery changes, the speed varies and the experience is profound.

And we’ll remember this when we are old and ancient

Though the specifics might be vague

And I’ll say your camisole was a sprightly light magenta

When in fact it was a nappy bluish grey

(July, July)

So what does all this have to do with The Decemberists you ask. Everything. First of all, it was in the spring of 2005 that I heard a song that broke my heart. It was called “We both go down together” and it was about two lovers committing suicide by jumping of “the cliffs of Dover.” The song was by was off their recently released “Picaresque,” which was the best record I’ve heard that year. Second of all, the Decemberists did with music what I wanted to do with journalism–they told intensely personal stories. On Picaresque they had the feel of medieval Gothic ballads set to slow strumming guitars, violins, mandolins and what have you. They were songs of death, fear, tragedy, but played in an oddly upbeat, yet appropriate way.

Here on these cliffs of Dover

So high you can’t see over

And while your head is spinning

Hold tight, it’s just beginning

(We both go down together)

I’m not ashamed to admit I discovered the Decemberists late (they started in 2001 and had produced plenty of music before “Picaresque”). I’m not ashamed because I embraced them so completely that I felt I never skipped a beat of their existence. Almost everything you read about the Decemberists will talk about Colin Meloy and his lyrics. The man loves big words, loves tragic stories, and loves performing them.

Pretty hands do pretty things when pretty times arise

Seraphim and seaweed swim where stick-limbed Myla lies

(Song for Myla Golberg)

I saw them the first time in Washington, DC and I loved it. The Decemberists are a soft band, they don’t “rock” in the traditional way. But the way the throw themselves into their more up tempo material is riveting and addictive. I left buzzing, wanting more–more stories, more songs, more of this experience. Here is the thing with a good story, or rather with how I react to one. My knees go weak, my heart starts racing and my mind starts screaming and running in circles. It engulfs, enthuses me and brings out unrelenting joy. I have a hard time explaining that I can divorce content from execution and intent. Tell me a sob story in which children die from cancer and I will sit there teary eyed and joyous. Because it was beautiful, because it did real life justice, because it taught me something valuable and it made me feel more connected to the world. Take the lyrics I treasure most from the Decemberists (see below). To me, the words of “Engine driver” speak to the need of telling the stories of your life and the lives of others–as a way of exorcising pain and pleasure, but also as a way to give something to the world.

And I am a writer, writer of fictions

I am the heart that you call home

And I’ve written pages upon pages

Trying to rid you from my bones

(Engine driver)

There is one more aspect to telling stories. Good stories can make you feel differently depending on the context. I married most bands to the context I discovered them in. I have a hard time separating The Arcade Fire from the small venue I first saw them in. Something Corporate will always conjure the smell of screaming teenagers smelling like vanilla. Guster will always be a road-trip soundtrack. When I brought the Decemberists to Romania in the summer of 2006, “We both go together” played and mean different things. So did “Engine driver.” And it is here that I first heard “O Valencia” and their latest album, “The Crane Wife.”

So be kind to your mother, though she may seem an awful bother,

and the next time she tries to feed you collard greens,

Remember what she does when you’re asleep.

(A cautionary song)

Before I left America, I went to two Decemberists shows back to back in Boston (no. 3 and 4). The first one was good, but my friend wasn’t fully into it, so we sat to the side, taking in the songs and the joyous crowd (both shows were sold out). But the second night I went up front to scream and sing my heart out. That night I kept thinking about leaving, thinking about the times I had in the US, the stories I heard and told, and the stories I will hear and tell in Romania. I was sad and overjoyed at the same time. It’s this time of one’s life when the Decemberists work best. They are an outlet for sadness and a tremendous source of joy.

I stepped out of the Avalon into the last snow of the season with tears in my eyes. As I slowly walked towards the subway, I couldn’t help repeating the mantra of one of the band’s closers, “Sons and daughters.” Somewhere, in an evil world, an unkind life, a bad day, the dark clouds will part. And as tragedy fades, joy eventually sets in. The Decemberists know that. It’s their story and it’s my story. And if you think about it a little, it’s your story, too.

See you in Vienna.

When we arrive, sons & daughters

We’ll make our homes on the water

We’ll build our walls of aluminum

We’ll fill our mouths with cinnamon now

Hear all the bombs, they fade away

Hear all the bombs, they fade away

(Sons and Daughters)

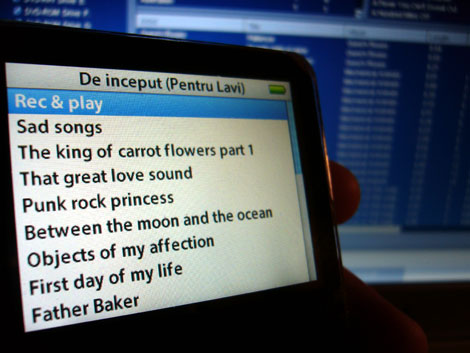

PS: Here is a Decemberists “best of,” fitting perfectly on an 80 minute CD. If assembling that sounds like too much work, stream the band at Hype-Machine or on their website.

1. The Decemberists – The crane wife 3 (4:20)

2. The Decemberists – The soldiering life (3:48)

3. The Decemberists – The sporting life (4:40)

4. The Decemberists – O Valencia (3:45)

5. The Decemberists – July, July (2:53)

6. The Decemberists – Summersong (3:27)

7. The Decemberists – Oceanside (3:29)

8. The Decemberists – Los Angeles, I’m yours (4:16)

9. The Decemberists – The engine driver (4:17)

10. The Decemberists – We both go down together (3:06)

11. The Decemberists – The chimbley sweep (2:53)

12. The Decemberists – Here I dreamt I was an architect (4:29)

13. The Decemberists – Red right ankle (3:29)

14. The Decemberists – A cautionary song (3:08)

15. The Decemberists – Sixteen military wives (4:54)

16. The Decemberists – Eli, the barrow boy (3:13)

17. The Decemberists – Song for Myla Goldberg (3:33)

18. The Decemberists – The mariner’s revenge song (8:47)

19. The Decemberists – Sons and daughters (5:13)

On Wednesday, Starbucks

On Wednesday, Starbucks